July 16: Driving from Estes Park, CO to Moab, UT

This was a spectacular drive, although sadly I have no pictures due to the Interstate’s inexplicable lack of scenic pullouts.

I drove down from Estes Park to Boulder to get on I-70 east. The Interstate climbed through Loveland Pass and then Vail Pass on its way through the Colorado Rockies. The mountain scenery was beautiful all the way.

Coming out into the western slopes of the mountains, the scenery changed— the mountains were still there but the dense pine forest gave way to scattered shrubs and yellowed grasses. I was heading into desert regions. The landscape continued to change as I drove on, eventually leaving the Interstate for highway 191 to Moab. Getting close to my destination, I entered an area of cliffs and spires of bright red rock. Just outside of town, I crossed a bridge over the Colorado River— now much larger than it was when I photographed it in meadow in RMNP just a few miles from its source.

July 17: Arches National Park

I have two days in Moab and two National Parks to cover. My initial plan was to see Arches today, and Canyonlands tomorrow. The park service website recommended an early start because Arches is popular and very busy. I got into the park around 7:30 and there were already plenty of cars heading in.

Arches starting flinging amazing geology at me right from the start: I realized after a couple of hours and a large number of photographs that I was using up the day and hadn’t even gotten to any actual arches yet.

|

|

My digital camera frustratingly fails to capture just how red these cliffs and towers are; they’re not tan as the pictures show. (Cameras never quite catch what the human eye sees. I could play with the color balance until they looked right to me, but would recolored photos be any more authentic than the camera’s original attempt?)

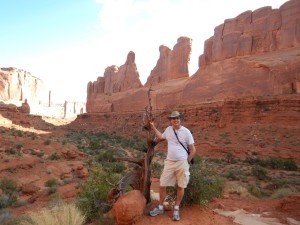

My first stop was a hiking trail running along the bottom of a canyon named “Park Avenue” because early explorers of the area thought the surrounding formations looked like New York skyscrapers.

|

|

|

|

|

|

This was still early morning so the canyon was mostly in shadow, which (again) bothers the camera more than the eye. But I did manage to catch a perfect shot as the sun appeared exactly in a notch on the canyon wall:

From Park Avenue I continued on the main road, coming to several more interesting formations:

Geologists believe, based on the shape of the rock faces and different degrees of erosion, that a double arch once connected sheep rock to the adjacent cliff face:

But they can’t be sure.

So what’s the story on the arches? 290 million years ago, the area of Arches National Park was under a landlocked inland sea which waxed and waned over millions of years as the climate fluctuated (I gather Utah’s Great Salt Lake is a remnant, though of a much more recent incarnation of this sometimes-sea). Evaporation when the sea retreated left behind salt deposits, eventually as much as a mile thick. When the sea returned it laid down sediments above the salt layer, again reaching a mile thick. Under the immense weight, the sediments were compressed into sandstone.

But the salt deposits couldn’t support the weight of rock above them. Under that kind of pressure, the salt liquefies and flows like a glacier over the bedrock beneath, sometimes piling up into salt domes, sometimes subsiding. This deformed and fractured the sandstone above in parallel fault lines which allowed water to seep down and gradually dissolve the salt. The result was sheets of sandstone, some being thrust upward and some subsiding, producing vertical walls called “fins.”

Sandstone erodes easily and wind and water carved the fins into unusual shapes. Different layers of different hardness eroded at different rates. In particular, it seems that any depression on one of the cliff faces tended to get steadily deeper and larger. In a solid mass like a mesa this would produce a cave-like depression. In the narrow fins, the depression eventually breaks all the way through and an arch is formed.

On a geological time scale, arches are temporary; erosion continues to enlarge the hole until the remaining sandstone is too thin to support its weight, and then it collapses. But at present, according to the park information, Arches National Park is home to more than 2000 such natural arches.

There’s a “baby arch” in the cliff next to where a double arch may have once existed at Sheep Rock:

Continuing on, more interesting formations— but apart from the “baby” I still hadn’t encountered any of the famous arches yet.

Continuing on, more interesting formations— but apart from the “baby” I still hadn’t encountered any of the famous arches yet.

Okay, it was about time I saw some of these famous arches. A side road led to a whole mess of ’em, in what’s called the “The Windows Section.”

Next up along the park road, a turn-off to “Delicate Arch.” Delicate Arch is the iconic image for the National Park, and also for the state of Utah (which puts a picture of Delicate Arch on its license plates). Surrounded by canyons that prevent getting a road near it, it can only be reached by a 1.5 mile (one way) hike. The park service recommends arriving at the trailhead by 7 AM in order to:

- Avoid the potentially dangerous heat of midday (temperatures in the mid 90s are typical for this time of year) and,

- Avoid the enormous crowds of people who ignore point 1 and keep the parking lot full all day.

Indeed when I reached it, the parking lot was entirely full. I drove on to where a slightly shorter hike (0.8) miles gives a distant view of the arch:

Although my original plan was to go to Canyonlands the next day, I decided to come back early in the morning and do the hike to Delicate Arch before heading on.

Although my original plan was to go to Canyonlands the next day, I decided to come back early in the morning and do the hike to Delicate Arch before heading on.

Continuing on, I passed the Fiery Furnace:

—named for the orange color the rocks take on at sunset, not because it’s actually hotter than anywhere else in the park. (In fact, according to the information display, the maze of narrow canyons are typically shady so it’s likely the coolest part of the park.)

—named for the orange color the rocks take on at sunset, not because it’s actually hotter than anywhere else in the park. (In fact, according to the information display, the maze of narrow canyons are typically shady so it’s likely the coolest part of the park.)

The final destination along the park road was another cluster of arches in a section called the Devil’s Garden, which includes Landscape Arch, another major park landmark.

I took way more pictures of a lot of other interesting things (including some really amazing landscape in general) but if I included them all, this post would run on like War and Peace. Time to move on.

July 18: Arches and Canyonlands

Yesterday was very hot, and I drank a lot of lukewarm water from refilling stations in the park. Today I came prepared with tasty bottled water nicely chilled in my cooler. But as I drove into Arches before 7 AM, it looked like rain rather than heat might be the issue of the day.

Still, I wasn’t going to let a little rain get in the way.

Still, I wasn’t going to let a little rain get in the way.

The trailhead to Delicate Arch was already crowded, but not yet full, so I parked, grabbed my hat and my water bottle, and set off.

Climbing out of the valley, the trail led up and across an outcropping of “Slipstone,” a specially hard variety of sandstone named for the fact that horse’s hooves had a hard time keeping traction on it. (Modern hiking boots do fine.)

A final climb up the side of a cliff, around the bend, and there’s Delicate Arch.

A final climb up the side of a cliff, around the bend, and there’s Delicate Arch.

The rain that threatened all morning helped keep the heat down during the hike, and it looked like the major downpour was going to pass this area by. It started sprinkling on the return hike, and the wind kicked up hard enough it could almost knock you over, but I got back to the TARDIS undrenched. On to my photographic repeat visit to Landscape Arch.

The rain that threatened all morning helped keep the heat down during the hike, and it looked like the major downpour was going to pass this area by. It started sprinkling on the return hike, and the wind kicked up hard enough it could almost knock you over, but I got back to the TARDIS undrenched. On to my photographic repeat visit to Landscape Arch.

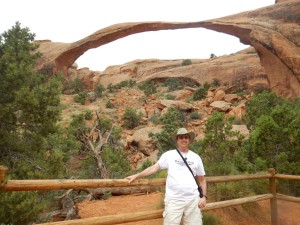

Landscape Arch has the longest span of any arch in the park. In fact, at 330 feet (according to the info display), it’s the longest natural span in the world.

Landscape Arch has the longest span of any arch in the park. In fact, at 330 feet (according to the info display), it’s the longest natural span in the world.

It’s hard to believe such a thin strand of rock can remain standing— and it won’t for much longer. Geologically speaking, Landscape Arch is on its last legs.

In 1991, park visitors picnicking under the arch heart cracking sounds overhead, and then ran for their lives when a shower of small rocks dropped from the arch. Moments later, they say a 60-foot long, 180 ton slab of rock peel off the right underside of the arch and crash to the ground. Fortunately no one was hurt, and the park service closed the trail that once led up under the arch. There’s been no rockfall since, but the trail remains closed because Landscape Arch could go at any time.

I hung around for a while to see if it was going to go while I was there. It didn’t, and I moved on. Time to head for Canyonlands National Park.

Just thirty-three miles from Arches (at its nearest point, anyway), Canyonlands National Park is made up of the same sandstone layers as its neighbor. But it didn’t suffer the fracturing that Arches, resting above a flowing salt deposit, did, and would probably be level ground now if the Green River and Colorado River, which meet in the center of the park, hadn’t carved deep canyons across it.

Just thirty-three miles from Arches (at its nearest point, anyway), Canyonlands National Park is made up of the same sandstone layers as its neighbor. But it didn’t suffer the fracturing that Arches, resting above a flowing salt deposit, did, and would probably be level ground now if the Green River and Colorado River, which meet in the center of the park, hadn’t carved deep canyons across it.

The Green River pours into the Colorado and they head off south together. On a map, the merging rivers form a Y shape that divides Canyonlands National Park into three sections. Due to the deep canyons, each section is inaccessible to the others, much like the north and south rim areas of the Grand Canyon. The section closest to Moab is the north section, between the two upper arms of the Y, a plateau called Island in the Sky. Southeast is The Needles, named for the formations the sandstone has been carved into there, and southwest is The Maze, an undeveloped area you can only enter by hiking (and hiking a long way, according to the map the closest road ends still 5 miles or so short of the park boundary).

The available area of Island in the Sky is smaller than Arches, and didn’t take too long to see. Given more time, I could have done more hikes here, but an afternoon was plenty to see the main sights.

|

|

The Shafer Canyon overlook is opposite the visitor center when you enter the park. The winding road into the canyon was originally a trail used by ranchers who grazed sheep on the grasses growing on the level ground above the canyon, and then led them down to shelter in the canyon at night. Narrow and treacherous, animals would often slip and fall to their deaths.

In the1950s during the uranium prospecting craze, miners widened the path and turned it into a road capable of car traffic— the geology of Canyonlands was the sort where uranium was likely to be found. After the creation of the national park in 1964, ranching and mining ceased, but the traces remain, and the road is now available for 4-wheel drive vehicles wanting to explore the canyon below.

Away from the canyon edges, Island in the Sky is flat-topped with vegetation that varies with the composition of the ground. Here, at Gray’s Pasture, is the open grassland that attracted ranchers and sheep herders.

Away from the canyon edges, Island in the Sky is flat-topped with vegetation that varies with the composition of the ground. Here, at Gray’s Pasture, is the open grassland that attracted ranchers and sheep herders.

|

Where the ground is more rocky, pinyon and juniper bushes cover it in “dwarf forests.” |

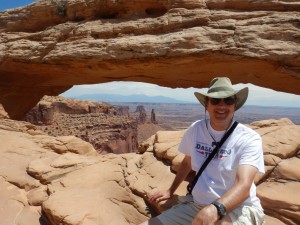

Canyonlands doesn’t have the “fins” of Arches, and so it doesn’t have the abundance of arches. It does have Mesa Arch, though. Perched on the very edge of the canyon, Mesa Arch provides a frame for a spectacular view.

More to see in Canyonlands:

But the real highlight of Canyonlands are the canyon overlooks. No road leads to the point where the Green and Colorado rivers merge, though there’s a hiking trail to Confluence Overlook that starts in The Needles section of the park. However, there are some great views of the separate canyons of the two rivers on their way to their meeting.

Green River Overlook. You can just see a little bit of the river itself, down inside its canyon.

Green River Overlook. You can just see a little bit of the river itself, down inside its canyon.

Grand View Point Overlook, showing the canyons carved by the Colorado and the various streams feeding into it. (The Colorado at this point is already so deep in its canyon it can’t be seen from here.)

Grand View Point Overlook, showing the canyons carved by the Colorado and the various streams feeding into it. (The Colorado at this point is already so deep in its canyon it can’t be seen from here.)

|

Monument Basin, rock formations carved by the river down in the canyon. |

| I zoomed my camera to its maximum, and I think this is a bit of the central canyon where the Colorado runs. |  |

After visiting the canyon overlooks, my quick tour of Canyonlands National Park was done. It was time to head back to the hotel.

And, hey, look! I’ve caught up to the present in my journal posts.

Tomorrow: Driving from Moab to the Grand Canyon

Let’s see what else that pesky Colorado river can get up to…