Source: “Charles Goodnight: Cowman and Plainsman” by J. Evetts Haley

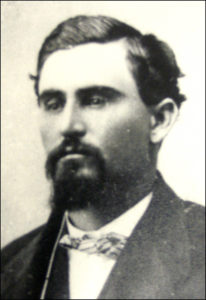

| One hundred and fifty years ago today, Charles Goodnight made history. He was thirty years old at the time and just getting started in the cattle business. He didn’t know he was making history; his only plan was to find a way to sell his cattle in the middle of a very tough time for West Texas ranchers.

When cattle ranching moved west, the breeds of cattle that European settlers brought with them proved unsuitable to the environment. European cattle were highly domesticated and required constant care: shelter in barns from bad weather, feeding in addition their own grazing, and so on. West Texas ranchers instead relied on a newly bred variety: the Longhorn. Longhorn cattle were, essentially, a reversion to the species’ pre-domestication wild type. They could be turned loose on the Texas prairie to fend for themselves. |

The ranching culture that developed in West Texas was built around the fact that the Longhorns roamed freely across the unfenced wilderness. Brands identified which cow in a mingled herd belonged to which ranch. The annual round-up was a massive, cooperative activity of all the ranchers in an area. Calves were assigned to the same owner as the cow they were following— presumed to be their mother though it wasn’t always.

Theft of the free-roaming cattle wasn’t hard, and although brands were designed to be difficult to fake or obscure, it was still possible. Ultimately the entire ranching culture highly depended on a strict honor system among the cowboys; and for that reason cattle thieves— rustlers— were the most hated kind of criminal, usually subject to swift vigilante justice if caught.

Charles Goodnight’s family moved into Texas when he was nine years old. As a young man, he became a scout with the Texas Rangers, fighting against both rustlers and attacks by the Comanche. The history of relations between white settlers and Native Americans in West Texas is as complicated and tragic as anywhere else across the continent; the short version is that settlers in the area had established a promising state of coexistence with the local Kiowa tribes, but the Comanche on one hand and Washington DC on the other would hear none of it. The locals of both ethnicities tried to make things work while caught in between these two empires, but to no avail. By Charles’ adulthood there was only hostility left.

The Civil War was barely noticed in the ranching country. For a while, the Texas Rangers came under the authority of the Confederate Army rather than the US Army, but they were still primarily involved with rustlers and Comanches rather than fighting against the Union. Reconstruction was another matter.

The punitive nature of Reconstruction policies meant corruption in local officials and indifference— or tacit approval— from higher Federal authorities. Federal officers in West Texas took bribes from gangs of rustlers, and in some cases joined forces with them to steal herds from any rancher they pleased, for their own profit. Any cattle a rancher managed to retain for sale they subjected to such overwhelming taxes (which never went on to the government but only straight into the local officials’ pockets) that making a profit on the sale was nearly impossible. Meanwhile the officials didn’t lift a finger to protect either herds or settlers from Comanche raids.

After the war, Charles had left the Texas Rangers and entered the cattle business. But faced with these difficulties, he came up with the idea that would change the American west forever: he decided to drive his cattle out of Texas altogether, selling them in New Mexico where Reconstruction policies weren’t in effect. Short cattle drives from rangeland to market were well established practice; but this type of long drive was a new idea.

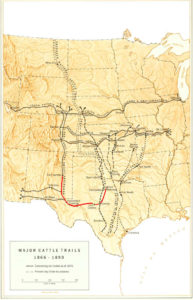

| Knowing the obstacles in the way, Charlie sat down and plotted a roundabout route from his ranch in Fort Belknap to Fort Sumner in New Mexico. More than twice the length of the direct route, Charlie’s trail was a long detour around Comanche territory, Federal outposts, and natural obstacles. It was the first leg of what would become known as the Goodnight-Loving trail.

The economic benefits of the long cattle drive would eventually prove so great that the practice survived the original conditions that led Charlie to the idea. Cattle trails proliferated and the cattle drive came to dominate the era of open-range ranching, until the spread of the railroads made it unnecessary and the spread of fences made it impossible. Though short-lived, it would also give rise to the American mythology of the archetypal cowboy and the Wild West through which he traveled. But while preparing this first drive, Charlie couldn’t know if it would even work. It was essentially a plan of desperation. He formed a partnership with his friend Oliver Loving, an older rancher who would also lend his name to the trail, and together they gathered a herd of 2,000 Longhorn cattle, only a tiny fraction of the number that would one day thunder along the cattle drives of the 1800s. They set out on June 6, 1866. |

There was one hazard that Charlie’s route could not avoid: the Pecos River.

Called by Native Americans “the crookedest river in the world,” the Pecos meandered so severely that tall tales spoke of a cowboy who once shot some game on the far bank, and swam across to recover the meat only to find that it had been on the same bank as himself all along.

Called by Native Americans “the crookedest river in the world,” the Pecos meandered so severely that tall tales spoke of a cowboy who once shot some game on the far bank, and swam across to recover the meat only to find that it had been on the same bank as himself all along.

Its wanderings carried the Pecos over the alkali plains of New Mexico, where it picked up enough salts to become briny and toxic. The main flow of the river was tolerable to drink, though unhealthy. But its marshy banks were covered in stagnant pools where evaporation concentrated the toxins to the point that animals could drop dead in the act of drinking. The marshes were also filled with soft bogs that could mire a cow beyond all hope of escape; the cowboys called them “quicksand.” Technically they weren’t but they were just as dangerous. For much of its length, the banks of the Pecos were steep cliffs, hazardous to try and climb down. Finally, the river ran through the heart of a desert, with no other water for miles around. Thirsty cattle would be drawn right to it.

Charles, Loving, and their hands were experienced enough with both cattle behavior and with the landscape to know the Pecos would be their great hazard. But only experience could have warned them of the magnitude of the trap that lay in their path, and experience in cattle drives of this type did not yet exist.

Charlie’s plan took their trail south to Concho, and then through the Castle mountains via the canyon called Castle Gap. From there, it would be twelve miles to Horsehead Crossing, the safest way across the Pecos. All told, from Concho to crossing, it would be eighty miles without water. The cattle would be thirsty, and if they caught the scent of water too soon, they’d stampede.

At Concho, Charles and the cowboys watered their cattle, getting them as full as possible. After that, for three days and nights the cowboys were in the saddle round the clock, with no rest, as they worked to keep control of the herd. By the time they emerged from Castle Gap, the Longhorns were suffering with thirst, and the twelve miles across the plain would be the danger zone.

That night, Charlie rode out ahead the twelve miles to the river, where he found a large number of deadly alkali pools. Throwing grass into the air to check the wind direction, he planned a route that would make sure the first scent of water the cattle received would come from Horsehead Crossing, their intended ford, rather than from this hazard. The next day the cowboys started the herd moving.

Disaster struck. The wind shifted, the cattle caught scent of water, and instantly they stampeded. Cursing, the cowboys tried to slow them down or turn them toward the crossing, to no avail. Desperate with thirst, the cattle would not be turned from that smell, and they’d run themselves to death before they slowed down. It was still twelve miles to the river.

Cattle started dropping dead of heat stroke along the way. The cowboys could do nothing for them. They kept trying to slow the herd, but nothing would do that. Worse lay ahead. Reaching the river, the herd stampeded over the steep banks, many breaking their necks. Others got mired in the quicksand. Those that reached the stagnant pools drank, and dropped dead from the poison on the spot. Others drowned in the river itself. The spare horses of the cowboys’ remuda were carried along and lost.

The cowboys, already exhausted, spent more days without sleep or rest trying to extricate their herd from the trap. They worked to dig out the steep banks, creating pathways for the cattle to climb out. They tried to pull mired cows out of the bogs. They struggled to control them, keeping them drinking only from the (relatively) safe waters of the main stream and not from the stagnant pools— but also to keep them from being swept away by the river currents while they did so.

By the time it was all over, and the cowboys got their herd away from the Pecos, seven hundred of their original two thousand cattle had died at the river. Looking back, Charles Goodnight formed a hatred for the Pecos as visceral as he had for any rustler. “That river,” he told his partner Oliver Loving, “is the graveyard of the cowman’s hopes.”

The name stuck. “Graveyard of the Cowman’s Hopes” would be the name of the Pecos River to ranchers during the era of the great cattle drives.

Future drives would benefit from experience. They would change their practices and their approach, and reduce their losses. But the Pecos River remained the greatest hazard in the path of the cattle drives, and was seldom if ever crossed without loss.

Despite their losses, when Charlie and Oliver arrived at their destination they were able to sell their reduced herd for a profit of $12,000— a fortune for ranchers in those days. Charlie’s concept had proven itself, and the era of the great cattle drives began.

The next year, in 1867, they started another drive and again the Pecos was the scene of disaster, though this time of another kind. At Horsehead Crossing they were ambushed by Comanches and Loving was wounded, eventually dying of his injuries. His last request was that Charlie take his body home for burial rather than burying him along the trail, a request that Charlie honored. After that, Charles Goodnight returned to the trail, eventually becoming one of the most successful ranchers of the nineteenth century, and the “founder of the Texas panhandle.” The Goodnight-Loving trail, still bearing the name of Charlie’s original partner as well as his own, would eventually extend all the way up to Montana.

It all started one hundred and fifty years ago today, June 6, 1866.

2 comments for “Crossing the Pecos”