Season 19 begins and the first task the series much achieve is presenting a new Doctor to the viewers. This is something every post-regeneration episode of the series has to do, and the way they’ve done it has varied. When Patrick Troughton took over the role, the series introduced him by way of a Dalek episode (one of the best, in my opinion), using the show’s most popular enemies to reassure viewers this was still Dr Who. The team of Barry Letts and Terrance Dicks used the same strategy to introduce Tom Baker, giving him a typical UNIT adventure to provide a familiar story for viewers to get used to the new Doctor. On the other hand, Jon Pertwee’s introduction marked the simultaneous transformation of the whole series: instead of reassurance that nothing had really changed, the series boldly declared that everything had.

Season 19 begins and the first task the series much achieve is presenting a new Doctor to the viewers. This is something every post-regeneration episode of the series has to do, and the way they’ve done it has varied. When Patrick Troughton took over the role, the series introduced him by way of a Dalek episode (one of the best, in my opinion), using the show’s most popular enemies to reassure viewers this was still Dr Who. The team of Barry Letts and Terrance Dicks used the same strategy to introduce Tom Baker, giving him a typical UNIT adventure to provide a familiar story for viewers to get used to the new Doctor. On the other hand, Jon Pertwee’s introduction marked the simultaneous transformation of the whole series: instead of reassurance that nothing had really changed, the series boldly declared that everything had.

Castrovalva does something rather odd. On the one hand, the story seems to take regeneration so completely for granted that not even Tegan, who only met the Doctor (in the context of the story) at most a few hours earlier, is surprised by it or ever once asks “Are we sure that’s actually the Doctor?” or “How could his face change like that?” (Granted, she saw the change happen, but so did Ben and Polly back when William Hartnell departed, and they still spent a good part of the next serial asking those two questions.) John Nathan-Turner believed that audiences by this point were accustomed to the idea of the Doctor changing, so there was no need for such questions— but the writing slips into a situation of having characters act according to what the writer knows rather than what the character would know.

On the other hand, at the same time the companions unrealistically take the idea of regeneration for granted, the story itself chooses to focus entirely on the process of regeneration itself. It had been previously established that it’s a traumatic event from which the new Doctor needs time to recover. Now the story revolves around the Master trying to exploit the Doctor’s weakened state by killing him before he has time to recover while the Doctor is in danger of dying even without any attack from the Master because “the regeneration is failing.”

Overall, this focus makes an interesting story. There’s no alien invasion here, and the Master has no scheme beyond trying to trap the Doctor. The titular village of Castrovalva is a quaint little place where nothing much is happening except what the Master turns out to be up to. The first episode and a half of the four parter takes place entirely inside the TARDIS. The Master has locked the TARDIS on course for the Big Bang (though that term is not used in the story) which not even the TARDIS can survive. With the Doctor wandering the corridors in a delirious state, Nyssa and Tegan desperately try to find a way to fly the ship themselves before they’re all destroyed.

Once out of that trap, they journey to Castrovalva, identified in the TARDIS data bank as a place where the natural environment has properties that allow Time Lords to recover from “cases of acute regenerative failure.” But the Master has another and subtler trap waiting at Castrovalva: not long after our heroes arrive, space begins folding in on itself and if they can’t get out quickly, they’ll be trapped inside it forever, while the Doctor will likely die from exposure to the complexities of folded space in his condition.

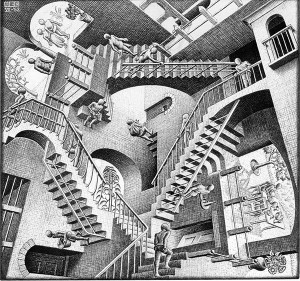

The story was inspired by the works of MC Escher, with set and costume designs based on various of his drawings, and the folding up of space meant to recall Escher’s Relativity (at right). Dr Who’s special effects let the story down at this point: the script imagined the episode 3 cliffhanger, when the Doctor realizes what’s happening to Castrovalva, to end on an image looking like Escher’s drawing. In practice, all they could do was superimpose a couple of unrelated images onto each other using chromakey, so what we see on screen is just a jumble.

The story was inspired by the works of MC Escher, with set and costume designs based on various of his drawings, and the folding up of space meant to recall Escher’s Relativity (at right). Dr Who’s special effects let the story down at this point: the script imagined the episode 3 cliffhanger, when the Doctor realizes what’s happening to Castrovalva, to end on an image looking like Escher’s drawing. In practice, all they could do was superimpose a couple of unrelated images onto each other using chromakey, so what we see on screen is just a jumble.

Still, it’s an interesting idea and works well in story terms. There’s an especially good scene when the Doctor tries to explain what’s happening to Ruther and Mergrave, two Castrovalvans who can’t see the effect because they’re part of it. He has Mergrave draw a map of Castrovalva and then point to the location of his house. “It’s here,” Mergrave says, pointing confidently. “And here, and here, and… here… also…” His face slowly registers shock. When the Doctor presses him, he tries to explain “It can be approached by many different routes.” But on his face you can see the shock as he realizes something is terribly wrong that he never noticed before.

On the down side, the script by Christopher Bidmead has the same weaknesses as Logopolis. It occasionally veers into pedantic conversations about Bidmead’s desired “hard science” grounding for Dr Who, and the “block transfer computations” introduced in Logopolis again play a central role in the story. It’s not a severe problem here. I can easily imagine Bidmead writing a script that spent page after page drawing the connection between mathematical recusion and the situation in Castrovalva and trying to put it all on a truly hard SF basis, but he doesn’t do that. He indulges a bit more pedantry than he should, but not too much more.

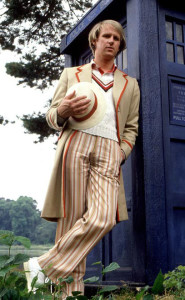

The Fifth Doctor

Castrovalva was actually the fourth story produced in season 19. The next three stories were shot first to give Peter Davison the chance to settle into the role, so he’d have a better idea of where he was going with his performance during this story, which revolves around the Doctor finding his new persona. It takes him all 4 episodes to settle down finally, after going through phases of unconsciousness, of mimicking the mannerisms of previous Doctors (Davison in particular does a splendid impression of Patrick Troughton at one point), of amnesia, inability to concentrate, and then finally in the last few minutes sticking his trademark stick of celery to his lapel and truly settling into himself.

Castrovalva was actually the fourth story produced in season 19. The next three stories were shot first to give Peter Davison the chance to settle into the role, so he’d have a better idea of where he was going with his performance during this story, which revolves around the Doctor finding his new persona. It takes him all 4 episodes to settle down finally, after going through phases of unconsciousness, of mimicking the mannerisms of previous Doctors (Davison in particular does a splendid impression of Patrick Troughton at one point), of amnesia, inability to concentrate, and then finally in the last few minutes sticking his trademark stick of celery to his lapel and truly settling into himself.

Following the examples of the past, the new Doctor is designed specifically to contrast the old one. John Nathan-Turner had met Peter Davison while working on All Creatures Great and Small, in which Davison played young veterinarian Tristan Farnon. While the Fourth Doctor was larger-than-life, loud, bold and over-the-top, the Fifth Doctor will be quiet and unassuming, often uncertain and with a distinct vulnerability to his persona. He won’t be in any way the superhero the Fourth Doctor played, and will often seem to just muddle through his adventures rather than dominating his adversaries with his brilliance and daring. In the event, writers would often have trouble knowing just how to write this version of the Doctor: as Davison describes it, they didn’t start figuring him out until he’d decided to leave the role. (But more on that when we come to it.)

His costume is an Edwardian-era cricket player’s uniform, with the addition of a tan frock coat with a stick of celery pinned to the lapel. (The official color of the frock coat is “fawn” but I doubt anyone but a costume designer or an obsessive reader of Doctor Who Magazine would think that when looking at it.) Davison has said he liked the cricket player idea but wished the costume looked a little less designed. He liked the idea that the Doctor just plucked clothes off some rack in the TARDIS wardrobe without much idea whether they went together or not. But going with a specific design was par for the course with JN-T’s determination to costume all his characters rather than dressing them. The Doctor finds most of the outfit in what appears to be a cricket team’s locker room inside the TARDIS (an intriguing location that includes a bulletin board with some notices pinned to it. You have to wonder if the TARDIS’ architectural configuration system came up with that detail, or did the Doctor once actually host a cricket league in there?) and the coat hanging on a rack outside. He finds the celery in Castrovalva, although we have to assume he changes it periodically after that.

The celery was another of JN-T’s ideas— he felt that every Doctor needed a “trademark” like Tom Baker’s long scarf.

Since I’m on costumes, I should mention the question marks on the shirt collar. They first appeared on the collar of Tom Baker’s shirt with his redesigned costume for season 18, but I forgot to mention them then. They were another of JN-T’s ideas. He felt that since we’d learned so much about Gallifrey and the Time Lords, the series had lost a lot of the mystery that once surrounded the Doctor. He thought the best way to make the character mysterious again was to have him wear question marks on his clothes. (This tells you something about JN-T’s creative instincts.) Script editor Chris Bidmead told him it was a bad idea, the costume designer told him it was a bad idea, Tom Baker told him it was a bad idea, but he was determined. The Doctor will have question marks on his outfits until the end of the Classic series— on the shirt collars of Four, Five and Six, and then the Seventh Doctor will wear a sweater patterned in question marks and carry an umbrella with a question mark handle.

Details

- Though he wrote this episode, Chris Bidmead ended his role as script editor with the end of season 18. The new script editor is Eric Saward, whose style of dialog will prove… interesting as it grows more exaggerated during his tenure. But I’ll say more later.

- As of the end of season 18 and the start of 19, we’ve got a crowded TARDIS with three companions: Adric, Nyssa and Tegan. Although not without precedent— the series began with a TARDIS crew of four— the times, the Doctor and the series have all changed since then. Instead of well-defined, different story roles as in the early years, the companion’s job now is pretty much to say “What is that, Doctor?” and then get into deadly peril. One companion can manage to weave a distinctive and interesting character around that basic story function, but there’s no narrative space for three. Almost immediately the writers will start to temporarily sideline one or more of them, and before the season’s done they’ll reduce the number permanently.

Next week:

“Four to Doomsday,” 4 episodes