“Is it to be the Doctor’s defense that he improves?” —The Valeyard

“Is it to be the Doctor’s defense that he improves?” —The Valeyard

Story

The prosecution has rested its case and it’s the Doctor’s turn to present his defense. Like the Valeyard, he chooses to do it by using the Matrix (the Time Lord repository of all knowledge) to show the court one of his adventures. He’s picked on from his future (presumably, only a possible future should the trial not end with his execution) and his point appears to be that he only gets involved in these events because of a direct request from recognized authority, thus demonstrating that if he’s acquitted, in the future he’ll only meddle when someone asks him to. On the screen:

The Doctor is traveling with a new companion, Melanie (Mel for short), when they receive a distress call addressed directly to the Doctor, from the luxury space liner Hyperion III. Arriving on board, it turns out the commander of the liner knows the Doctor from a previous encounter but he’s not the one who sent the distress call. Soon a passenger is apparently murdered and the evidence suggests he’s the one who sent the call, although since he’s pulverized in a waste disposal chute the Doctor has no chance to find out who he really was. Before long, though, more bodies are piling up and the Doctor finds himself cast in the role of detective in a whodunnit right out of Agatha Christie. Everyone is a suspect and everyone is up to something shady. Among the suspects is a group of scientists whose shady scheme is that they’re transporting some very large plant pods they claim are a new highly productive food crop they’ve developed, but which in reality are something else. With everyone occupied with the murder mystery, no one has time to pay much attention when the pods are found empty— but not all the bodies that pile up are the work of our murderer. Monsters called Vervoids have hatched out of the pods and are lurking in the air ducts, taking out the humans one by one.

Of course the Doctor finds the killer (I won’t spoil it by saying who it is), and then destroys the monstrous Vervoids (I won’t spoil it by saying how), but back in the Trial it appears his choice of evidence has backfired: since the Vervoids were an artificially-created species and the only ones in existence were aboard the Hyperion, the Valeyard charges the Doctor with genocide for destroying them.

Review

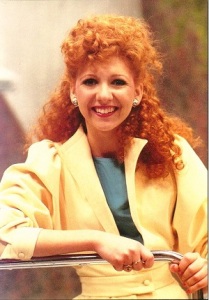

This story is famous in Dr Who lore mainly for the monster design, which is, let’s say, the most questionable design choice since Tom Baker blew into a “pseudopod” during Creature from the Pit. You can look at the picture above and draw your own conclusions, but I’ll just mention that when Doctor Who Magazine put a picture of a Vervoid on its cover, the magazine drew criticism for obscenity.

We’ll just leave that where it is and look at the story.

With this third story in the Trial season, we suddenly get a picture of a structure that Eric Saward and JN-T must have intended for the season. We started with an adventure of the Doctor’s from some time before the Trial started, then the one he was in the middle of when the Trial began, and now one from his future. Past, present and future— like some attempt at the classic Christmas Carol formula. Unfortunately, no attention at all is drawn to this, nor do they use the three to show us anything like a story or character arc spanning the three different points in the Doctor’s life, so when you notice it you can only go, “Meh.”

Terror of the Vervoids was written by Pip and Jane Baker, and it’s probably the best— well, least awful— of their contributions to Dr Who. The central murder mystery of the story plays reasonably well, and when the Doctor confronts the killer and lays out the clues we can see that it actually plays fair with the viewer, as a mystery should: the clues that led the Doctor to the killer were visible to us as well, and we could figure it out ourselves, but like a good mystery we don’t until the Doctor lays it out for us.

On the other hand, the Vervoid plot really falls flat. So much about it fails to make sense. The Vervoids are a newly-created species, the ones that emerge from the pods are newborns and the first ever of their kind. I can just about accept that they’d have a language— if it’s innate— and that the ever-present TARDIS translation circuits would let us understand it. But they do things like trade villain dialog about invading Earth, they know to hide in air ducts, they listen to what the humans are doing and plan accordingly, and at one point a Vervoid covers up killing a passenger by turning on a shower so the person outside the cabin thinks the victim is still alive inside. And you can only say, “Wait a minute, wait a minute, where did Vervoids learn what showers arr and how to turn them on?”

Late in the story the Doctor states that the Vervoids are simply acting on pure instinct, and it would have been far better for the story if it really played that way: if the Vervoids were mere monsters, instead of intelligent creatures talking to each other about standard-issue alien invasion schemes.

Finally, the destruction of the Vervoids plays far too rushed. Once the “real” killed is revealed, the story’s really over. There’s only a few minutes left to take care of the monsters. The Doctor provides a quick solution and the episode could have let it play out equally quickly, but instead the Bakers try to give us a climactic action scene that attempts to show how difficult it was to pull off— but only has about thirty seconds to do it, so it just feels anticlimactically easy. (I could also point out that the solution is scientific nonsense even by Dr Who’s freewheeling standards, but the new series recently gave us Kill the Moon and forced us all to redefine our standards on that score.)

Meanwhile the Trial storyline strains new levels of incredulity. It’s normal for a murder mystery on TV or in a movie to play with the viewer by showing scenes of the killer doing things while never letting us see his face— but why in the world would the Time Lord’s Matrix be so coy? Like any good mystery the episode plays lots of these games on us for dramatic purposes, and while they work (or would work) if the story was just a story, they really rub our noses in how nonsensical is the idea we’re watching this as courtroom evidence compiled by the all-seeing repository of knowledge.

I will give the story this: there’s less a problem with the Trial taking us out of it than previously. The Trial scenes interrupt the story less frequently than in the previous stories this season, and in an odd way the issue of evidence tampering becomes less harmful because it becomes more explicit. In Mindwarp, the Doctor’s loss of memory kept him (and us) unsure of what had been altered and what hadn’t, so we could never be sure if we were watching the “real” adventure. This time, though, although the events are in the Doctor’s future, he watched them prior to coming to court as part of preparing his defense, so he knows exactly when someone (obviously, but not yet provably, the Valeyard) has altered them. The alterations are confined to two specific moments that are pointed out to us as such: when the Doctor ignores a vital clue Mel gives him (and in the Trial he points out he didn’t ignore it), then later when the killer sabotages some equipment on the ship but on screen the Doctor’s image is substituted— actually a more clever way of concealing the killer’s identity than having the Matrix use coy camera angles for no good reason. When we’re told specifically “This scene was altered, and here’s exactly how,” we’re not left guessing and we know we can trust the rest of what we see.

Finally, Pip and Jane Baker just can’t bring themselves to trust their viewers, and have a painful habit of telling us things they’ve already shown us, just to make sure we don’t miss them. In one cliffhanger, the Hyperion is being steered directly toward a black hole, threatening everyone on board. We’ve known through the story the ship was making a dangerous passage past the black hole in question, the person doing it says very clearly what he’s doing and that he’s trying to kill himself and take the ship with him, and we get a pretty decent (for the time) special effects shot of the ship heading for the black hole. But before going to the end credits, we’re taken back to the Doctor saying “He’s piloting the ship directly toward the black hole!” Yes Doctor, we noticed already. Earlier in the story, one passenger is shown reading Murder on the Orient Express just in case we might fail to notice what genre of story we’re in. Pip and Jane just can’t help doing this kind of thing.

New Companion

It’s an interesting choice to use the “future adventure” idea to skip over having to meet the Doctor’s new companion: when we first see Melanie Bush (her surname was never mentioned on screen, but is there in the official character description) she and the Doctor are already traveling together. I say “interesting” but it’s not necessarily a good choice. When the Valeyard accuses the Doctor of trying to gloss over Peri’s death by bringing us Mel already aboard the TARDIS, you can’t help but think that’s what the show is trying to do. (Writing tip: if you’ve got a problem in your storytelling, fix it rather than thinking you can skate by with having a character lampshade it.)

It’s an interesting choice to use the “future adventure” idea to skip over having to meet the Doctor’s new companion: when we first see Melanie Bush (her surname was never mentioned on screen, but is there in the official character description) she and the Doctor are already traveling together. I say “interesting” but it’s not necessarily a good choice. When the Valeyard accuses the Doctor of trying to gloss over Peri’s death by bringing us Mel already aboard the TARDIS, you can’t help but think that’s what the show is trying to do. (Writing tip: if you’ve got a problem in your storytelling, fix it rather than thinking you can skate by with having a character lampshade it.)

JN-T and Eric Saward always planned to show the Doctor’s actual first meeting with Mel in the premiere of the following season, but for reasons we’ll discuss next week that never happened. To date, there’s no canonical account of how she and the Doctor first met.

Mel is a squeaky-voiced, eighties-haired and eighties-costumed aerobics instructor who when we first meet her has somehow cajoled the Doctor into working out on an exercise bike in the TARDIS console room. She’s forcing him to drink a glass of carrot juice when the Hyperion’s distress call mercifully arrives. This sort of silliness aside, Mel is a rather refreshing change after a long run of unusual companions: Tegan and Peri, who both spent most of their time complaining and arguing with the Doctor, Turlough who actually wanted to kill him, before that the boy genius Adric and the alien Nyssa, Time Lady Romana, robot dog K-9, savage Leela— you have to go all the way back to Sarah Jane Smith for the last example of what we’d normally think of as the “traditional” companion. Mel is no Sarah Jane (let’s make no mistake about that) but it is kind of nice to finally have a companion who seems to just be having a lot of fun seeing the universe with the Doctor.

Mel is played by Bonnie Langford, best known before Dr Who as a successful stage actress, who was coming off playing the lead in Peter Pan (the stage play traditionally having an adult female play the boy Peter) as well as a part in Les Miserables.

Next Week:

“The Ultimate Foe,” 2 episodes as the Trial itself finally takes center stage, and concludes.