July 22

Another driving day to start off, but today the drive was (comparatively) short. Around three hours from Grand Canyon to the south entrance to Petrified Forest National Park. It was an enjoyable drive through mostly flat countryside, at first in thick Ponderosa pine forest then gradually thinning out and giving way to desert grassland, greener than usual because they’ve gotten some of the rare desert rain just lately.

I arrived at Petrified Forest around noon and planned to spend the afternoon going through the park. I’m only here overnight before driving on, so the afternoon was all I had for this stop on my tour.

Petrified Forest National Park, at first glance, isn’t as obviously spectacular as Gradn Canyon or Arches or the other stops on my road trip. Its allure is in knowing what it is you’re seeing: a snapshot into what’s sometimes called “deep time.” The pictures I took don’t do it justice; what’s fascinating about it is what the mind sees, not the eye. (Although some straightforward visual wonders were also to be found.)

I may have the perfect combination of interests to really appreciate this park. I’m a writer and have been told by people who’ve read my first novel that I have a certain amount of imagination. And I’m a biologist who got my degree in evolutionary biology. Put those two together, and today I was walking through a Lost World.

Around 225 million years ago, in the Triassic period, this was the scene of a slow-moving river, spreading out into marshes and swamps all around. Imagine the Louisiana bayou, perhaps, or the Florida everglades, but it wasn’t really like either one. The life here was so different from our modern world that if transported there, you might think you were on another planet.

Around 225 million years ago, in the Triassic period, this was the scene of a slow-moving river, spreading out into marshes and swamps all around. Imagine the Louisiana bayou, perhaps, or the Florida everglades, but it wasn’t really like either one. The life here was so different from our modern world that if transported there, you might think you were on another planet.

A dense forest of conifers rose from the swampy wetlands, but not the pine trees that today cover the Rocky Mountains. On the ground grew dense tangles of ferns and mosses— no flowering plants had yet appeared on Earth, nor any grasses. Fallen trees carried downstream in the river choked the stream with piles of rotting logs, causing the swamps to spread. Regular seasonal floods deposited silt and gravel, swiftly burying whatever fell.

Something had happened to the Earth 25 million years earlier— quite recently in geological time. The extinction of the dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous is perhaps the most famous extinction in paleontology, but the mass extinction at the end of the Permian period was worse. 96% of all species on Earth at the time were wiped out. Now, in the middle of the Triassic, the survivors have diversified. The therapsids had in fact already appeared in the Permian; they were among the survivors. But something else was about to come along and put an end to the early Triassic diversity.

If the extinction of the dinosaurs is a fascinating mystery, their success is more so. In the middle of the Triassic, reptiles or mammal-like reptiles of numerous different families occupied the land. But once the dinosaurs appeared, they took over: by the end of the Triassic, all large land animals were dinosaurs. Everything else was swept away; the large therapsids were gone, and their descendants, the first mammals, never got bigger than modern mice or rats until after the dinosaurs were gone. Dinosaurs would rule the Earth for 180 million years. What was the reason for such dominance? Perhaps the fossils at Petrified Forest, dating from the first appearance of the dinosaur family, will someday provide the answer.

So this was the world I was walking through when I walked through the sand and gravel of what is today a desert, the river that flowed for tens of millions of years now gone.

Fossilization is very rare; even when conditions are ideal, most fallen trees (and fallen animals) rot away, are consumed and scattered by scavengers, and leave no trace behind. Even here, where conditions were ideal for fossilization for millions of years running, probably only a tiny minority of the trees that floated down the swampy river have been preserved. But a tiny minority of trees that populated a dense forest for millions of years is still a lot of petrified trees!

|

|

The river silt compressed into mudstone, a rock even softer and crumblier than sandstone. The petrified trees embedded in it were far harder. So as the mudstone erodes away in the present desert climate, the petrified trees come to the surface, or appear sticking out of hillsides, until they break in pieces and fall downhill.

In the desert, rains are rare but torrential when they come. When a very soft rock like mudstone is exposed to those conditions, the result is a landscape known as “Badlands.” There are lots of badlands around the world, but Petrified Forest offers spectacular examples.

|

|

The way the soft stone erodes looks exactly like a pile of loose soil or clay piled up by a bulldozer and subjected to a couple of days of rain— except for the distinct colored bands of different layers, showing that these hills are no jumble produced by digging up the ground, but undisturbed sediments that have eroded away. Touch the hills, and sure enough they’re rock, not mud or clay.

|

|

|

Outcrops of harder sandstone get carved by erosion into the strange shapes that sandstone tends to form, sticking out of the mud-like hills of the softer material. |

|

|

There’s also more recent history to be seen in Petrified Forest National Park. The Ancestral Puebloans make another appearance; the ruins of a small pueblo are found in the park, as is “Newspaper Rock,” covered in petroglyphs left by the vanished tribe.

|

|

And historic Route 66 once ran through the park— making Petrified Forest the only National Park in the system to have once had a bit of Route 66 in it. During the heyday of the “Mother Road” from the twenties to the fifties, Route 66 brought considerable fame, and more crowds than today, to Petrified Forest.

North of the former Route 66 is the section of Petrified Forest called the Painted desert, for the color of the sediments making up its badlands.

|

|

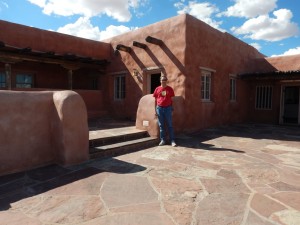

The end of the Route 66 era also brought an end to the once-successful and famous Painted Desert Inn. It fell into disrepair until it was named a historic landmark in the 80s. It’s recently been restored as a museum with many of the original furnishings.

And so comes an end to my visit to Petrified Forest National Park. Tomorrow, I continue on— my longest driving day yet as I go on to the last destination of my Epic July Road Trip.

Tomorrow: Driving to Carlsbad Caverns