Day 25: July 4 (posted July 6)

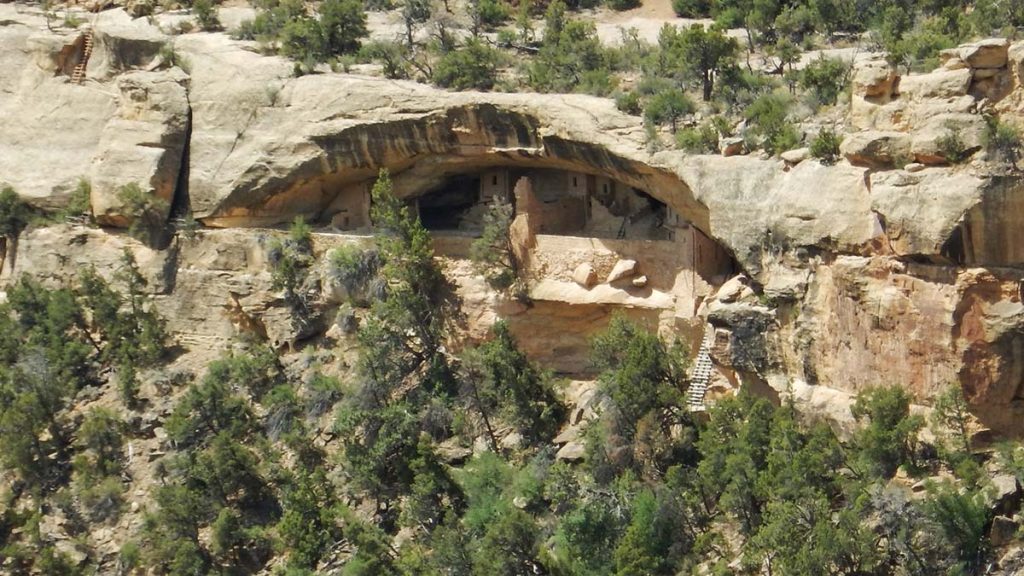

Much like Yellowstone’s hot springs, seeing every single Mesa Verde cliff dwelling and archaeological site in person is pretty cool— but as photographs, they look pretty repetitive. So just as with Yellowstone, I’ll try to pick out the highlights for today’s journal entry.

Mesa Verde became a national park in 1906. It was the 6th national park, and the first to center on a cultural rather than natural point of interest. Its founding was primarily the work of a woman named Virginia McClurg, a newspaper reporter from Colorado Springs in the late 19th century, who made it her life’s work to see the cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde preserved. She enlisted the help of the Colorado General Federation of Women’s Clubs, who in turn formed the Colorado Cliff Dwellings Association. Formed entirely from women’s clubs, the association’s motto was Dux femina facti— Latin for “Women lead the way.”

Turning from the history of the park to the history of the site, Mesa Verde was home to a thriving population now known as the Ancestral Puebloans for around a thousand years. They weren’t an isolated community; the entire “Four Corners” region of present-day Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah was well-populated by Puebloan farms and villages, all in communication with each other. Changes in art and architecture happened at the same time all over the region, showing they remained one unified culture. There were networks of trade across the whole continent: archaeologists have found sea shells from California and feathers from South American birds among the artifacts at the sites.

As I set out to explore today, I learned that the closure of one of Mesa Verde’s two scenic roads, and almost all of its hiking trails, wasn’t just due to the current extreme fire risk: there have been fires breaking out every day. So far they’ve all been contained before spreading, but the rangers can’t have people out on the hiking trails where today’s new fire, springing up who knows where, might put them in danger. The closure of the visitor centers, museum, and cliff dwellings themselves, however, is due to the epidemic.

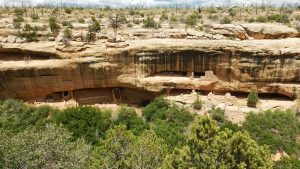

I’m going on too long before getting to the pictures. With so much closed, all I could do was tour the open scenic road and see what could be seen from the overlooks. Which was plenty: a number of sites on the mesa top are open and accessible by short trails, and there’s a downloadable app with an audio tour that I followed.

The Ancestral Puebloans practiced “dry farming”— growing crops without irrigation, relying on the annual snowfall and brief summer rains to provide all the moisture needed, but they needed more water for drinking and to make the mortar used to build their structures.

From the Far View Sites I drove on to the Mesa Top Loop, a road with winds its way around a number of sites that lets you see the development of Ancestral Puebloan culture in roughly chronological order.

The superimposed villages show the development of stone building: the earlier village had walls a single layer of stone thick, the later one had double-thickness walls. The people were looking to build sturdier, more permanent structures. Park service text suggests that fire was an issue, just as it is today: many of the old wood-frame buildings were abandoned after burning down.

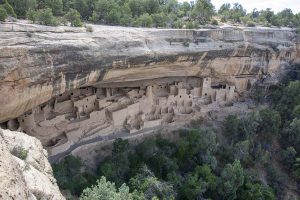

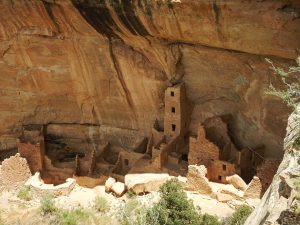

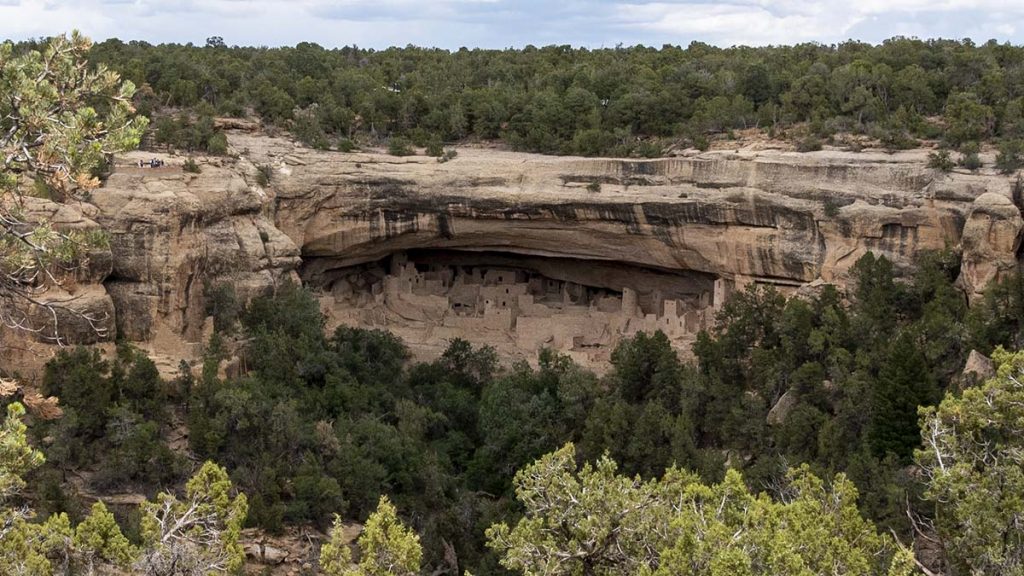

Okay, I’ve been going chronological in order to build suspense for the really amazing sites: the cliff dwellings.

For all the effort that obviously went into building them, the cliff dwellings were a late and short-lived feature of the culture. They first began to build and move into the cliff dwellings around 1200 AD, after nearly a thousand years thriving on the mesa top, but by 1300 AD they abandoned the cliff dwellings as well and left the area altogether.

Why did the Ancestral Puebloans abandon the area, especially after the enormous effort of building all these cliff dwellings? The story used to be that they “mysterious vanished” around 1300AD, but in fact they didn’t— we know exactly where they went, they migrated south to the present-day pueblos where they still live today, using much of the same architecture as back then (even some of the same buildings: the Taos Pueblo, still occupied today, was founded right around that time).

There is a mystery about why they left. The modern Puebloans’ oral histories tell of leaving the Mesa Verde area, but the only reason they give is that “it was time.” Depletion of game, running out of timber as the last trees were cut down to make farmlands, prolonged drought, and conflict with other tribes (or within different clans of the Puebloans themselves) have all been suggested, and all of those things might have been going on at once, so that the place where this culture had thrived for a thousand years was simply no longer suitable.

Balcony House, one of the later cliff dwellings constructed, may provide a clue: the vertical wall dividing the site down the center cuts off half of it from access to the “seep spring,” the water source found at the back of almost all the cliff dwelling alcoves. Water had become such a precious resource that the people living here were in conflict with their own clan over access to it. It could be that all the cliff dwellings were built to move the people close to, and defend, the remaining water sources.

Balcony House, one of the later cliff dwellings constructed, may provide a clue: the vertical wall dividing the site down the center cuts off half of it from access to the “seep spring,” the water source found at the back of almost all the cliff dwelling alcoves. Water had become such a precious resource that the people living here were in conflict with their own clan over access to it. It could be that all the cliff dwellings were built to move the people close to, and defend, the remaining water sources.

Whatever was happening, whatever had gone wrong, it looks like the cliff dwellings were a last-ditch attempt to hang on in the Mesa Verde area. But it wasn’t enough. By 1300 AD, not only the mesa but the entire Four Corners region had been completely abandoned, as the Puebloans migrated south to where they still live today.

Okay, I’ve droned on long enough and I’ve been more textbookish than usual for what’s supposed to be a trip journal. It’s just a really cool story, and I love that the park’s exhibits let you follow it chronologically, and actually see the ancient people’s culture develop and change over time as you walk or drive from one site to the next.

But getting back to journal matters— with so much closed, today I saw all of Mesa Verde that’s open. I have another day to fill tomorrow. What will I do with it?

Trip Report:

Miles driven today: 29.4

Total miles so far: 4700.6